Shoulder dystocia

| Shoulder dystocia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Suprapubic pressure being used in a shoulder dystocia | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Symptoms | Retraction of the baby's head back into the vagina[1] |

| Complications | Baby: Brachial plexus injury, clavicle fracture[2] Mother: Vaginal or perineal tears, postpartum bleeding[3] |

| Risk factors | Gestational diabetes, previous history of the condition, operative vaginal delivery, obesity in the mother, an overly large baby, epidural anesthesia[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Body fails to deliver within one minute of the head[2] |

| Treatment | McRoberts maneuver, suprapubic pressure, Rubin maneuver, episiotomy, all fours, Zavanelli's maneuver followed by cesarean section[3][2] |

| Frequency | ~ 1% of vaginal births[2] |

Shoulder dystocia occurs after vaginal delivery of the head, when the baby's anterior shoulder is obstructed by the mother's pubic bone.[3][1] It is typically diagnosed when the baby's shoulders fails to deliver despite gentle downward traction on the baby's head, requiring the need of special techniques to safely deliver the baby.[2] Retraction of the baby's head back into the vagina, known as "turtle sign" is suggestive of shoulder dystocia.[3][1] It is a type of obstructed labour.[4]

Although most instances of shoulder dystocia are relieved without complications to the baby, the most common complications may include brachial plexus injury, or clavicle fracture.[2][1] Complications for the mother may include increased risk of vaginal or perineal tears, postpartum bleeding, or uterine rupture.[3][1] Risk factors include gestational diabetes, previous history of the condition, operative vaginal delivery, obesity in the mother, an overly large baby, and epidural anesthesia.[2]

Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric emergency.[3] Initial efforts to release a shoulder typically include: with a woman on her back pushing the legs outward and upward, pushing on the abdomen above the pubic bone.[3] If these are not effective, efforts to manually rotate the baby's shoulders or placing the woman on all fours may be tried.[3][2] Shoulder dystocia occurs in approximately 0.2% to 3% of vaginal births.[5] Death as a result of shoulder dystocia is very uncommon.[1]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]One characteristic of a minority of shoulder dystocia deliveries is the turtle sign, which involves the retraction of the fetal chin against the mother's perineum after the head is delivered.[6][7] This occurs when the baby's shoulder is obstructed by the maternal pelvis or high in the pelvis.

Complications

[edit]

Possible complications include:

- Neonatal complications:

- Brachial plexus injuries[8] (2.3% to 16%)

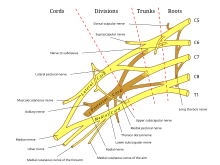

- One complication of shoulder dystocia is damage to the upper brachial plexus nerves. These supply the sensory and motor components of the shoulder, arm, and hands. A brachial plexus injury doesn’t always mean shoulder dystocia happened. Studies have shown that not all brachial plexus injuries are caused by shoulder dystocia and that these injuries can have multiple causes[5][9]. How well a baby recovers depends on the type of injury they have. For example, 64% of babies with injuries at the C5–C6 or C5–C6–C7 levels fully recovered by 6 months, but only 14% of those with C5–T1 injuries did.[5] Some brachial plexus injuries may be associated with Horner syndrome, diaphragmatic paralysis, and facial nerve injury[5] or may lead to:

- Clavicular or humeral fractures

- Hypoxia,[8] leading in some cases to:

- Brachial plexus injuries[8] (2.3% to 16%)

- Maternal complications:[10]

- Postpartum bleeding (11%)

- Perineal lacerations that extend into the anal sphincter (4th degree laceration) (3.8%)

- Pubic symphysis separation

- Neuropathy of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

- Uterine rupture

Risk factors

[edit]Even though there are several known risk factors, shoulder dystocia can happen to anyone and cannot be reliably predicted or stopped from happening.[10] Doctors should know the risk factors to watch for in high-risk deliveries and be ready to handle this complication in any delivery.[10]

Pre- labor risk factors:[3][10]

- History of shoulder dystocia

- Maternal Obesity

- High estimated fetal weight > 4.5 kg (fetal macrosomia)

- Maternal diabetes (2–4 fold increase in risk) (Gestational diabetes)

- Short in stature/ Small or abnormal pelvis[11]

During labor risk factors:[3]

- Need for oxytocin/pitocin (Augmentation of labor)

- Prolonged first or second stage of labor

- Arrest of labor

- Instrumental delivery

For women with a previous shoulder dystocia, the risk of recurrence is at least 10%, therefore, doctors do not recommend C-sections for everyone with a history of it.[10] Instead, they suggest making a careful delivery plan based on medical details, future pregnancy goals, and what the patient prefers.[10]

Prevention

[edit]Because shoulder dystocia is more common in cases of larger babies (fetal macrosomia) or mothers with diabetes, researchers have studied whether inducing labor, before the baby reaches a weight that might cause medical concerns, can help lower the risk. However, studies looking at how induction affects shoulder dystocia in full-term pregnancies with suspected larger babies have shown mixed results with studies reporting increased rates cesarian deliveries without reducing the risk of birth injuries[12], while others reported no effect on cesarian delivery rates and a reduction in rates of shoulder dystocia[13]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend delivery before 39 weeks unless medically indicated, and discourages inducing labor just because macrosomia is suspected, regardless of how far along the pregnancy is[10].

The benefit of elective cesarian delivery has also been studied in cases of suspected fetal macrosomia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends considering elective C-sections for women without diabetes if their baby is estimated to weigh at least 5,000 g, and for women with diabetes if their baby is estimated to weigh at least 4,500 g[10].

Management

[edit]Preparation

[edit]Practicing with obstetric simulations is a helpful way for health care providers to prepare for shoulder dystocia as it is a rare but serious event. Research shows that simulations improve communication, the use of maneuvers, and how events are documented[14]. A training program that included lessons on a specific response plan for shoulder dystocia, along with repeated practice simulations and discussions afterward, led to a significant drop in brachial plexus palsy cases—from 10.1% before training to 4.0% during training, and then to 2.6% after training[15]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends practicing with simulations and following shoulder dystocia protocols to improve team communication and the use of maneuvers, which could help lower the chances of brachial plexus palsy caused by shoulder dystocia[10].

Procedures

[edit]The steps to treating a shoulder dystocia can be outlined by the mnemonic HELPERR[16]:

- Help: Call for additional help from obstetrics, nursing, anesthesia, and pediatrics. The patient should also be instructed to breathe and do NOT push[16][10].

- Evaluate for episiotomy: Not necessary in most cases but should be considered if additional room is needed to perform maneuvers[10].

- Legs: McRoberts maneuver

- Pressure: Suprapubic pressure

- Enter maneuvers. Perform rotational maneuvers

- Remove the posterior arm

- Roll over on all fours

*Pushing on the fundus is not recommended as it can make the shoulder more stuck and can lead to tearing of the uterus[1][10].

A number of labor positions and maneuvers are sequentially performed in attempt to facilitate delivery. These include:

First-line Maneuvers

[edit]- McRoberts maneuver; it is usually the first maneuver performed as it is easy, noninvasive, and effective[10]. It involves hyperflexing the mother's legs tightly to her abdomen. This widens the pelvis, and flattens the spine in the lower back (lumbar spine)[17]. This maneuver is usually combined with applying suprapubic pressure or Rubin I by having an assistant apply pressure above the pubic bone with the palm or fist, directing the pressure on the anterior shoulder both downward (to below the pubic bone) and laterally (toward the fetus's face or sternum)[10]. Together, McRoberts maneuver and suprapubic pressure relieves about 58% of shoulder dystocias[18].

Second-line Maneuvers

[edit]- Rubin II; a rotational maneuver where pressure is applied to the back of the front shoulder to rotate the back shoulder counterclockwise[19][20][21].

- Wood's screw maneuver; another type of rotational maneuver where pressure is applied to the front of the back shoulder to rotate the back shoulder clockwise until delivery of the front shoulder (somewhat the opposite of Rubin II maneuver)[19][20][22].

- Jacquemier's maneuver (also called Barnum's maneuver), or delivery of the posterior shoulder first, in which the forearm and hand are identified in the birth canal, and gently pulled[19].

- Gaskin maneuver involves moving the mother to an all fours position with the back arched, widening the pelvic outlet.[23][24]

Extraordinary Measures

[edit]- Zavanelli's maneuver, which involves pushing the baby's head back in (internal cephalic replacement) followed by a cesarean section;[25]

- Cleidotomy, which is causing intentional clavicular fractures, thus reducing the diameter of the shoulders to pass through the birth canal;[2]

- Maternal symphysiotomy, which makes the opening of the birth canal laxer by breaking the connective tissue between the two pubes bones;[2]

- Abdominal rescue, described by O'Shaughnessy, where a hysterotomy facilitates vaginal delivery of the impacted shoulder.[26]

*Before these measures are attempted the above maneuvers should be attempted again[8]

Documentation

[edit]The time when shoulder dystocia is diagnosed and when the delivery is completed should be recorded. It is also important to document details about how the shoulder dystocia was managed, including key facts, findings, and any outcomes[17]. The Royal College of Obstetrician and Gynecologist recommends recording[8]:

- Type of delivery: Spontaneous or instrumental (include station and reason if instrumental).

- Time interval: Between delivery of the head and body.

- Shoulder positions: Identify which shoulder was anterior or posterior.

- Maneuvers: Record timing and sequence of maneuvers performed.

- Personnel present: Include all medical and nursing staff in attendance.

- Neonatal assessment: Document Apgar scores, cord blood gases, fractures, or reduced arm movement.

- Episiotomy: Note whether one was performed or not.

- Traction details: Timing, duration, and angle of applied traction.

- Infant condition: Include any findings related to fractures or movement issues.

- Patient communication: Summarize information provided to the patient or family.

Epidemiology

[edit]Shoulder dystocia occurs in approximately 0.2% to 3% of vaginal births and can happen to anyone.[3][10] However, research suggest that larger baby size, also known as fetal macrosomia, increases the risk of shoulder dystocia. For babies weighing less than 4 kg, the likelihood of shoulder dystocia is about 1%. This risk rises to approximately 5% for babies weighing between 4 and 4.5 kg and increases further to 10% for babies weighing over 4.5 kg.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Gherman, Robert B.; Gonik, Bernard (2009). "Shoulder Dystocia". The Global Library of Women's Medicine. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10137.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dahlke, JD; Bhalwal, A; Chauhan, SP (June 2017). "Obstetric Emergencies: Shoulder Dystocia and Postpartum Hemorrhage". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 44 (2): 231–243. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2017.02.003. PMID 28499533.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Shoulder dystocia" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Buck, Carol J. (2016). 2017 ICD-10-CM Standard Edition - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 108. ISBN 9780323484572.

- ^ a b c d "Executive Summary: Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 123 (4): 902–904. April 2014. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000445582.43112.9a. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 24785634.

- ^ Bennett, Barbara B. (September 1999). "Shoulder Dystocia: An Obstetric Emergency". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 26 (3): 445–458. doi:10.1016/S0889-8545(05)70089-9. PMID 10472064.

- ^ Floyd, Randall C.; Smeltzer, James S. (2012), "Shoulder dystocia", Clinical Maternal-Fetal Medicine (2 ed.), CRC Press, doi:10.1201/9781003222590-11, ISBN 978-1-003-22259-0

- ^ a b c d "Shoulder Dystocia (Green-top Guideline No. 42)" (PDF). RCOG. Retrieved 2024-05-24.

- ^ Gherman, Robert B.; Ouzounian, Joseph G.; Goodwin, T.Murphy (May 1999). "Brachial plexus palsy: An in utero injury?". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 180 (5): 1303–1307. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70633-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Practice Bulletin No. 178 Summary: Shoulder Dystocia". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 129 (5): 961–962. 2017-05-01. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002039. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 28426613.

- ^ Thayer, Sydney Marie; Owens, Sarah N.; Skeith, Ashley; Valent, Amy; Caughey, Aaron B. (May 2019). "Prevalence of Shoulder Dystocia by Maternal Height and Diabetes Status [5T]". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 133 (1): 214S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000559106.44163.fd. ISSN 0029-7844.

- ^ Sanchez-Ramos, Luis; Bernstein, Sara; Kaunitz, Andrew M. (November 2002). "Expectant Management Versus Labor Induction for Suspected Fetal Macrosomia". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 100 (5, Part 1): 997–1002. doi:10.1097/00006250-200211000-00030. ISSN 0029-7844.

- ^ Boulvain, Michel; Thornton, Jim G (2023-03-08). Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group (ed.). "Induction of labour at or near term for suspected fetal macrosomia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (3). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000938.pub3.

- ^ Crofts, Joanna F.; Fox, Robert; Ellis, Denise; Winter, Catherine; Hinshaw, Kim; Draycott, Timothy J. (October 2008). "Observations From 450 Shoulder Dystocia Simulations: Lessons for Skills Training". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 112 (4): 906–912. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181865f55. ISSN 0029-7844.

- ^ Grobman, William A.; Miller, Deborah; Burke, Carol; Hornbogen, Abby; Tam, Karen; Costello, Robert (December 2011). "Outcomes associated with introduction of a shoulder dystocia protocol". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 205 (6): 513–517. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.002.

- ^ a b Stitely, Michael L.; Gherman, Robert B. (June 2014). "Shoulder dystocia: Management and documentation". Seminars in Perinatology. 38 (4): 194–200. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2014.04.004.

- ^ a b Stitely, Michael L.; Gherman, Robert B. (2014-06-01). "Shoulder dystocia: Management and documentation". Seminars in Perinatology. Shoulder dystocia and neonatal brachial plexus palsy. 38 (4): 194–200. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2014.04.004. ISSN 0146-0005.

- ^ McFarland, M.b.; Langer, O.; Piper, J.m.; Berkus, M.d. (1996). "Perinatal outcome and the type and number of maneuvers in shoulder dystocia". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 55 (3): 219–224. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(96)02766-X. ISSN 1879-3479.

- ^ a b c Gherman, Robert B.; Gonik, Bernard (2009). "Shoulder Dystocia". The Global Library of Women's Medicine. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10137. ISSN 1756-2228.

- ^ a b Stitely, Michael L.; Gherman, Robert B. (2014-06-01). "Shoulder dystocia: Management and documentation". Seminars in Perinatology. Shoulder dystocia and neonatal brachial plexus palsy. 38 (4): 194–200. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2014.04.004. ISSN 0146-0005.

- ^ Baxley EG, Gobbo RW (April 2004). "Shoulder dystocia". Am Fam Physician. 69 (7): 1707–14. PMID 15086043.

- ^ "Fetal Dystocia: Abnormalities and Complications of Labor and Delivery: Merck Manual Professional". Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ^ Murray, Michelle; Huelsmann, Gayle (2008-12-15). Labor and Delivery Nursing: Guide to Evidence-Based Practice. Springer Publishing Company. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0-8261-1803-5.

- ^ Murray, Michelle; Huelsmann, Gayle (2008-12-15). Labor and Delivery Nursing. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8261-1803-5. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Fernandez H, Papiernik E (1990). "Manoeuvre de Zavanelli : application à la rétention de tête dernière au détroit supérieur : à propos d'une observation" [The Zavanelli maneuver: use during breech retention of the head in the birth canal. Apropos of a case]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) (in French). 19 (4): 483–5. PMID 2380511.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy MJ (October 1998). "Hysterotomy facilitation of the vaginal delivery of the posterior arm in a case of severe shoulder dystocia". Obstet Gynecol. 92 (4 Pt 2): 693–5. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00153-7. PMID 9764668. S2CID 42443502.

- ^ Menticoglou, Savas (November 2018). "Shoulder dystocia: incidence, mechanisms, and management strategies". International Journal of Women's Health. 10: 723–732. doi:10.2147/ijwh.s175088. ISSN 1179-1411. PMC 6233701. PMID 30519118.